Recently, a couple of advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) wrote in The Hill about “Why we should stop worrying and learn to love the national debt.” This piece was brought to us by the same crowd who had the idea for a trillion-dollar coin a few years ago. The authors lay out objections to common concerns about the growing US debt and deficit. While there are kernels of truth in what they say, they miss the bigger picture; namely that money is ultimately a claim on real goods, services, and resources.

The authors are perfectly right to point out that the US need never have a technical default either, because it can always print the necessary dollars to repay its debts. But as economists have long pointed out, what really matters to investors is not the number of dollars they receive, but the value or purchasing power of those dollars.

This, by the way, is why there are huge numbers of buyers for US debt and relatively few buyers for Mexican (interest of 8 percent or more), Brazilian (interest of 10 percent or more), or Kenyan (interest of 8 percent or more) government debt. These countries have no risk of technical default because they can always print more of their currency. So why are relatively few people willing to buy their debt even when they offer much higher interest rates? It’s because buyers in the bond market recognize a different kind of risk: currency devaluation, which can erode their real wealth.

US Treasuries have high demand because the US has a good track record of maintaining the value of its currency – at least relative to other countries.

But what about the claim that the Federal Reserve can simply buy up any and all debt issued by the federal government, no matter how large? The Fed can also set the price at which it does so simply by offering anything up to the face value of the bond (which is the equivalent of lending at a zero percent rate of interest). This is also true, but the MMTers fail to reckon with the real-world implications.

While exchanging Treasury liabilities for Fed liabilities does not increase the overall amount of liabilities, it assumes that new (possibly huge) liabilities were created in the first place. When the federal government spends more money than it receives, it issues a liability, an IOU, in the form of a Treasury bond. And the federal government has been issuing such IOUs at a startling, and frightening, rate over the past two decades — but especially over the past five years.

US federal debt as of July 2025 was over $36.5 trillion. Five years ago, it was less than $27 trillion. Ten years ago, it was about $18 trillion.

“Not to worry!” say the MMTers, “Don’t you realize that while Treasury bonds are IOUs for the government, they are assets for whoever holds them? So you see, there is really no net debt being created, only debt and a corresponding asset — one that happens to be safe and useful at that.”

This is where ignoring reality creates problems. It is true, in a sense, that the issuing of a debt creates a corresponding asset. And it is also true that this asset is “safe” from technical default risk. It will be repaid in dollars. However, investors will not buy them for only these reasons. They want real returns on their investment. They give up real consumption or investment opportunities today for the prospect of greater real consumption or investment opportunities in the future.

And when it comes to the real value of dollars or Treasury debt, how much debt is created matters, whether or not the Fed monetizes it with newly created currency. When deficits and debts grow rapidly, the likelihood of currency devaluation increases. This is why people are less interested in Mexican, Brazilian, and Kenyan government debt.

“But who needs private lenders anyway?” the MMTers say, “The Federal Reserve can fund the government all by itself — and at a lower interest rate too!”

Yes, the Fed can do that.

But consider the real economic effect of doing so. When the Treasury borrows from the public, fewer dollars are available for private investment or consumption while more dollars become available for public investment or consumption. Changes in private spending in the economy are largely offset by changes in government spending.

That is not the case when central banks buy government debt with newly created currency. In that case, private spending and government spending do not offset each other. Private spending does not decline even as public spending increases. Yet there are not more real goods, services, or resources in the economy than before. As a result, funding large amounts of public spending with newly created currency leads to greater overall spending, and a heightened bidding war in the economy.

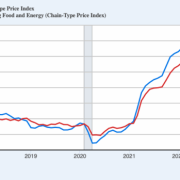

This drives prices up and leads to what we call inflation.

MMTers have some clever syllogisms and tautologies that they use to argue national deficits and debts are benign. Unfortunately, several of their premises fail to account for reality. The national debt really is a problem, as anyone attempting to rein in federal spending will tell you. Interest payments have become one of the biggest federal budget items and will almost certainly continue to grow.

If Congress fails to rein in this runaway spending, it’ll have to turn to the central bank for financing. Though the dollars are there, the real goods and services are not. As a result, we will all experience the very real effects of inflation.