Joseph (Jake) Klein’s book Redefining Racism dives deep into a narrow slice of the history of the Social Justice Fundamentalism (SJF) movement: the redefinition of the term “racism.” He starts in 1960s Detroit, and traces the history through decades of SJF activists from Robert Terry to Robin DiAngelo, to describe how the term “racism” got redefined away from “racial prejudice or discrimination” and into “prejudice plus power.”

The redefinition Klein describes isn’t trivial. For one thing: if racism simply means racial prejudice, then most SJF activists are racist. In Is Everyone Really Equal?, for instance, Robin DiAngelo and Özlem Sensoy ascribe derogatory characteristics to whole groups of people based on their immutable characteristics. Saria Rao and Regina Jackson dedicate their book White Women: Everything You Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to Do Better to “all Black, Indigenous, brown, and non-white girls, women, and non-binary identifying folks who are sick and tired of white women’s bullshit.” A 2019 Washington Post article asks, “Can black and white women be true friends?“, a question that the author (a black woman) answers with a qualified “no.”

Under the traditional definition of racism, this is all terribly racist. But when SJF activists redefined racism to mean “prejudice plus power,” they accomplished two ends.

First, because in the SJF worldview only members of a dominant group (whites, males, straight people, etc) can have power, they neatly redefined the term so that they themselves couldn’t be racist. Rao, Jackson, and other authors who weren’t straight white men were said to lack institutional power, and so under the new definition, their prejudice couldn’t be labeled as racism. Second and more importantly, they came up with a way to accuse all white people of being racist, without that claim in itself being considered evidence of racism. In many ways, the rapid spread of SJF ideas into mainstream discourse wouldn’t have been possible if the term “racism” hadn’t been redefined to exclude SJFs speaking derogatorily about groups based on those groups’ shared immutable characteristics. So the history of how and why “racism” was redefined seems like a worthy target of investigation.

Possibly the biggest insight that Klein has uncovered is that this movement has always been one of (primarily) white people talking to other white people. He notes that the most prominent antiracists of the past 60 years have almost all been white. Pat Bidol, a high school educator who first redefined the term “racism” to be about prejudice plus power, was white. Robert Terry, whose book For Whites Only was the White Fragility of its time, was white. So were James Edler, Judith Katz, and most of the other big names of the antiracist movement in the second half of the 20th century.

The SJF movement has always tried to build credibility by claiming that it’s speaking for minorities. In the “Reading Guide” for White Fragility, for instance, DiAngelo writes that “this book and its arguments build on antiracism scholarship and activism that people of color have written for generations.” But of course this isn’t true. DiAngelo draws so heavily from the works of Bidol, Terry, Edler, Katz, and others that, as Klein writes, “her decision not to cite any of them could arguably be described as plagiarism.”

In 2017, More In Common published a taxonomy of seven different political tribes in the United States, ranging from “Progressive Activists” (those on the far-left) to “devoted conservatives” (those on the far-right). The study found that 80 percent of progressive activists are white. Only three percent are black. Contrary to the claims of DiAngelo and others, this movement is mostly white people talking to other white people about minorities. Klein makes an important point that it’s been this way for the past sixty years.

The other big benefit of Klein’s work is that he documents the extent to which we’ve been here before. The SJF movement hasn’t changed much in the past 60 years, and many of the worst characteristics of the recent “Great Awokening” have their echoes in prior generations of SJF scholarship and activism.

Then as now, the movement latches onto the ideas of a fringe group of black political extremists while ignoring the views of most black Americans. Klein tells the story of how the Detroit Industrial Mission, one of the earliest antiracist organizations, brought in black separatists as well as black extremists who called the NAACP an “Uncle Tom” organization, supported the riots that were tearing the city apart, and derided democracy as “trash.”

“It’s important to note,” Klein writes, “that these views were not even close to mainstream in the black community. In 1968, only 1 percent of Detroit blacks favored ‘total separation’ of the races while 88 percent supported integration. Only 3.5 percent approved of a separate black nation.”

Meanwhile, while black militants advocated riots and violence, Klein reports that most black Americans in Detroit wanted law and order and an end to the riots.

The same pattern can be seen today. Black Lives Matter, for instance, is a Marxist organization that called to defund the police. These views are not shared by a majority of black Americans, who broadly speaking support a strong police presence in their neighborhoods.

Then, as now, the anti-racism movement seems to correlate with (and perhaps cause) lower levels of mental health. Klein quotes Edler, one of the champions of this movement in the 1970s, who complained that his new “knowledge” of racism was making him miserable: “every place I go, I end up being upset; upset at television, the news broadcasts, at the newspaper, at jokes, at teachers, and even at friends.” Edler would cut off relationships with friends who didn’t agree with him, which may have contributed to his reported frustration and loneliness.

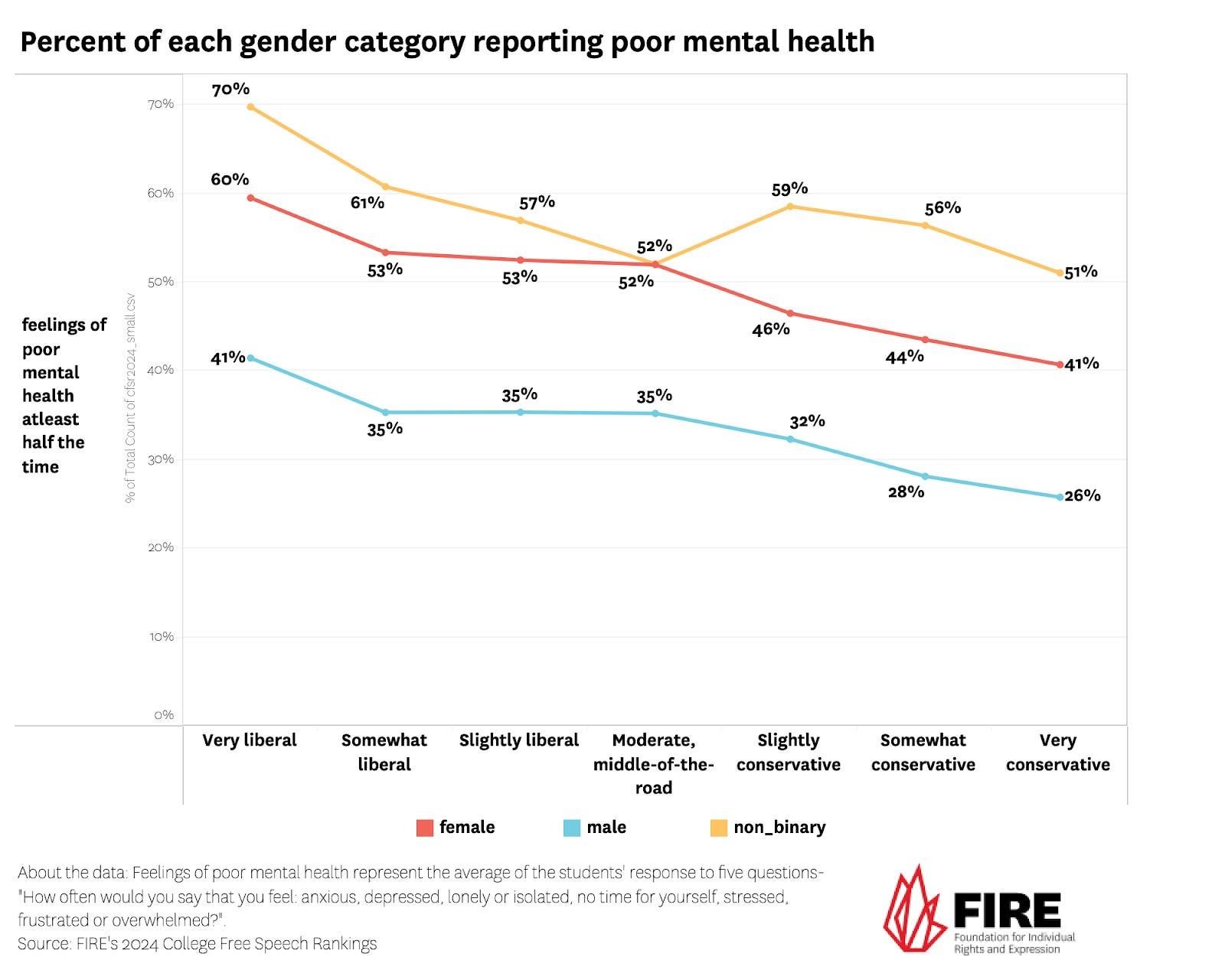

We see the same pattern today. Greg Lukianoff and Andrea Honeycutt published a study suggesting that “very liberal” students were substantially more likely to report low levels of mental health as compared with moderate or conservative students.

Source: Eternally Radical Idea

Just like Edler, these social justice warriors aren’t being liberated by their far-left ideology. Instead, they’re finding that it takes an emotional toll.

In case after case, I found myself reading Klein’s book and seeing echoes of the modern-day SJF movement in his stories. We truly have been here before.

But for all that it makes an important point, I’m not sure that I would recommend this book as an entry point for someone just starting to learn about the SJF movement. I read and write about SJF for a living, and even I found the book to be dense and full of minutiae. There’s so much detail it can feel overwhelming, especially because much of the detail feels like ‘inside baseball’ that doesn’t contribute meaningfully to the narrative sweep of the story.

Redefining Racism is extremely well-researched, but sometimes Klein includes so many details on the page that they bog down the story he’s telling. That’s a shame, because underneath those minutiae is a story that’s vital to tell.